$3.35 Billion ‘Account Tax’: When EOA Becomes a Systemic Cost, What Can AA Bring to Web3?

However, behind these seemingly high-dimensional structural changes, a more fundamental yet long-ignored issue is emerging: the account itself is becoming a systemic risk source for the entire industry.

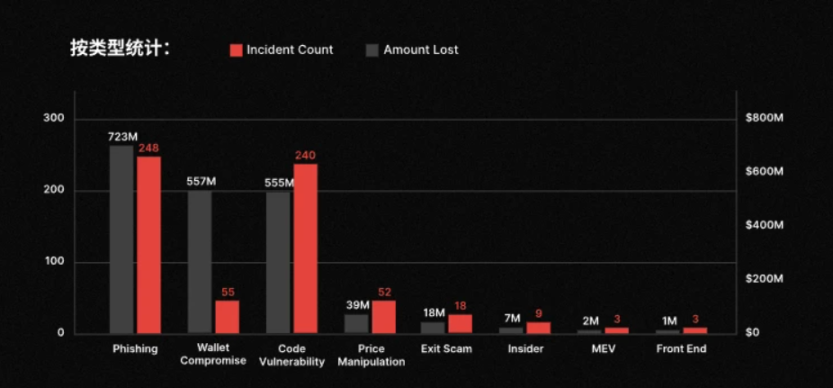

A recent security report from CertiK provided a rather glaring figure: a total of 630 security incidents occurred in Web3 throughout 2025, resulting in cumulative losses of approximately $3.35 billion. If we stop at this aggregate number, it might just be another annual reiteration of the severe security landscape. But upon further dissecting the types of incidents, a more alarming trend becomes apparent:

A significant portion of the losses did not stem from complex contract vulnerabilities, nor from direct protocol breaches, but were concentrated at a more primitive and unsettling level: phishing attacks—248 phishing-related incidents occurred throughout the year, causing about $723 million in losses, even slightly exceeding code vulnerability attacks (240 incidents, approximately $555 million).

In other words, in a large number of user loss cases, the blockchain did not malfunction, cryptography was not broken, and transactions fully complied with the rules.

The real problem lies with the accounts themselves.

1. EOA Accounts: Becoming Web3’s Biggest ‘Historical Problem’

Objectively speaking, whether in Web2 or Web3, phishing has always been one of the most common ways people lose funds.

The difference is that Web3, by introducing smart contracts and irreversible execution mechanisms, often leads to more extreme outcomes once such risks materialize. To understand this, we must return to Web3’s most fundamental and core account model: the EOA (Externally Owned Account).

Its design logic is extremely pure: the private key equals ownership, the signature equals intent. Whoever holds the private key possesses full control over the account. This model was undoubtedly revolutionary in the early stages, bypassing custodial institutions and intermediary systems to return asset sovereignty directly to the individual.

However, this design also implies an extremely radical premise: in the EOA assumption, users will not be phished, will not make operational errors, and will not make wrong judgments under fatigue, anxiety, or time pressure. Once a transaction is signed, it is considered an expression of the user’s genuine, fully understood intent.

Reality is clearly not so.

The frequent security incidents in 2025 are the direct result of this assumption being repeatedly breached. Whether it’s being induced to sign malicious transactions or completing transfers without sufficient verification, the commonality lies not in technical complexity, but in the account model’s inherent lack of fault tolerance for human cognitive limitations (Extended reading: From EOA to Account Abstraction: Will Web3’s Next Leap Occur in the ‘Account System’?).

A typical scenario is the long-standing on-chain Approval authorization mechanism. When a user grants approval to an address, they are essentially allowing the other party to transfer assets from their account without requiring further confirmation. In terms of contract logic, this design is efficient and concise; but in practical use, it frequently becomes the starting point for phishing and asset draining.

For instance, the recent $50 million address poisoning incident: the attacker did not attempt to breach the system but constructed a “similar address” with highly similar first and last four characters, inducing users to complete transfers hastily. The flaw of the EOA model is laid bare here: it’s genuinely difficult for anyone to ensure they can verify a string of dozens of meaningless alphanumeric characters within an extremely short time, every single time.

Ultimately, the underlying logic of the EOA model dictates that it doesn’t care if you were deceived; it only cares about one thing: whether you “signed.”

This is precisely why successful address poisoning cases have frequently made headlines in recent years. Attackers don’t need to resort to laborious tactics like 51% attacks; they simply need to create a sufficiently similar address for poisoning and wait for users to carelessly copy, paste, and confirm.

After all, an EOA cannot determine if this is an unfamiliar address never interacted with before, nor can it recognize if this operation significantly deviates from historical behavioral patterns. To it, this is just a legal, valid transaction instruction that must be executed. Thus, a long-ignored paradox becomes unavoidable: Web3 is extremely secure at the cryptographic level, yet exceptionally fragile at the account level.

Therefore, from this perspective, the $3.35 billion in industry losses in 2025 cannot be simply attributed to “users not being cautious enough” or “hackers upgrading their methods.” Instead, it is a signal that when the account model is pushed to the scale of real finance, its historical liabilities begin to manifest collectively.

2. The Historical Inevitability of AA: A Systemic Correction for Web3’s Account Architecture

After all, when significant losses occur under circumstances where the system is “operating entirely by the rules,” that in itself is the biggest problem.

For example, in CertiK’s statistics, phishing attacks, address poisoning, malicious approvals, mistaken signatures, and similar incidents almost all share a common premise: the transactions themselves are legal, signatures are valid, and execution is irreversible. They neither violate consensus rules nor trigger abnormal states; they even appear perfectly normal on a block explorer.

It could be said that, from the system’s perspective, these are not attacks but correctly executed user instructions.

Ultimately, the EOA model compresses “identity,” “authority,” and “risk assumption” into a single private key. Once a signature is completed, identity is confirmed, authority is granted, and risk is assumed in a one-time, irrevocable manner. This extreme simplification was an efficiency advantage in the early stages. However, as asset scale, participant demographics, and use cases evolve, it begins to reveal significant institutional flaws.

Especially as Web3 gradually enters a state of high-frequency, cross-protocol, always-online usage, accounts are no longer just cold wallets for occasional operations. They now serve multiple functions like payments, approvals, interactions, and settlements. Under such conditions, the assumption that “every signature represents a fully rational decision” is increasingly difficult to uphold.

From this angle, the reason address poisoning repeatedly succeeds is not because attackers are smarter, but because the account model offers no buffer against human fallibility—the system won’t ask if this is an entity never interacted with before, won’t judge if the amount significantly deviates from historical behavior, and won’t trigger delays or secondary confirmations due to anomalous operations. For an EOA, as long as the signature is valid, the transaction must be executed.

In fact, the traditional financial system has long provided the answer. Whether it’s transfer limits, cooling-off periods, abnormal freezes, permission tiers, or revocable authorizations, they all essentially acknowledge a simple yet realistic fact: humans are not always rational, and account design must reserve buffer space for this.

It is precisely against this backdrop that Account Abstraction (AA) begins to reveal its true historical position. It is more akin to a redefinition of the account’s essence, aiming to transform an account from a passive tool that executes signatures into an entity capable of managing intent.

The core lies in the fact that under AA’s logic, an account is no longer merely equivalent to a private key. It can have multiple verification paths, can set differentiated permissions for different types of operations, can delay execution when anomalous behavior appears, and can even regain control under specific conditions.

This is not a departure from the spirit of decentralization but a correction for its sustainability. True self-custody does not mean users must bear permanent consequences for a single mistake; it means that, without relying on centralized custodians, the account itself possesses error-prevention and self-protection capabilities.

3. What Can Account Evolution Bring to Web3?

The author has reiterated a statement multiple times: “Behind every successful scam, there will be a user who stops using Web3, and the Web3 ecosystem, without any new users, will have nowhere to go.”

From this dimension, whether it’s security firms, wallet products, or builders in other industry sectors, they can no longer view ‘user error’ as individual negligence. Instead, they must shoulder the systemic responsibility of making the entire account architecture sufficiently safe, comprehensible, and fault-tolerant in real-world usage scenarios.

Therefore, the historical role AA can play lies precisely here. In short, AA is not merely a technical upgrade of accounts but an institutional adjustment of the entire security logic.

This change is first reflected in the loosening of the relationship between accounts and private keys. For a long time, seed phrases have almost been regarded as the passport to Web3 self-custody. However, reality has repeatedly proven that this single-point key management method is not user-friendly for most ordinary users. AA, by introducing mechanisms like social recovery, decouples the account from being strongly bound to a single private key. Users can set multiple trusted guardians; when a device is lost or a private key becomes invalid, control over the account can be restored through verification.

Even when AA is combined with Passkey, we can construct an experience that truly approaches people’s intuitive understanding of account security in the traditional financial system (Extended reading: Web3 Without Seed Phrases: AA × Passkey, How to Define Crypto’s Next Decade?).

Equally important is AA’s reconstruction of transaction friction. In the traditional EOA system, gas fees constitute an almost implicit barrier for all on-chain operations. AA, through mechanisms like Paymaster, allows transaction fees to be sponsored by third parties or paid directly using stablecoins.

This means users no longer need to prepare a small amount of native tokens specifically to complete a transfer, nor are they forced to understand complex gas logic. Objectively speaking, this gasless experience is not just a nice-to-have; it is one of the key conditions determining whether Web3 can move beyond its early adopter circle.

Furthermore, AA accounts leverage the native capabilities of smart contracts to bundle previously fragmented multi-step operations into a single atomic execution. Taking a DEX trade as an example: in the past, it required steps like approval, signing, trading, and signing again. Under an AA account, these operations can be completed in one transaction—either all succeed or all fail—saving costs and avoiding invalid losses due to mid-process failures.

A deeper change is reflected in the malleability of account permissions themselves. AA accounts are no longer a binary structure of “either full control or complete loss of control.” Instead, they can have fine-grained permission management logic, much like real-world bank accounts. Different amounts correspond to different verification strengths; different counterparties correspond to different interaction permissions; they can even restrict accounts to interact only with specific safe contracts through whitelists/blacklists.

This means that even in the extreme case of a private key leak, the account itself still possesses a buffer space, preventing assets from being completely drained in a short period.

Of course, it must be emphasized that the evolution of account security does not rely entirely on the comprehensive rollout of the AA account system. Existing wallet products can and must also undertake part of the correction for the EOA model.

Take imToken as an example. Its address book function saves commonly used, trusted addresses. This means that during transfers, the account no longer relies entirely on the user’s immediate judgment of a hash string but prioritizes selection from the existing address book, significantly reducing transfer risks caused by manual copying, pasting, or misjudging similar addresses.

Equally important is the industry consensus principle that has gradually formed in recent years: “What You See Is What You Sign” (WYSIWYS). Its core is not about displaying more information but ensuring that the content a user signs must align with the action they see, understand, and expect, rather than being compressed into an indiscernible hash data segment.

Centered around this principle, imToken has implemented structured parsing and readable presentation of signature content at various critical stages involving signatures, including DApp login, transfers, token swaps, and approvals. This allows users to truly understand what they are agreeing to before confirmation. This design does not alter the irreversibility of transactions but introduces a necessary layer of rational buffer before signing occurs—an indispensable step in the maturation of the account system.

From a broader perspective, the evolution of AA accounts is actually reshaping the foundational assumptions for Web3’s next phase of development, enabling the chain to truly possess the conditions for hosting a large-scale, real user base. Otherwise, no matter how complex the protocols or how grand the narratives, they will ultimately be repeatedly breached by the most primitive question: whether ordinary users dare to keep their assets on-chain long-term.

It is precisely in this sense that AA is not a bonus feature for Web3 but more like a passing grade. It determines not whether the experience is good, but whether Web3 can evolve from an experimental system primarily for tech enthusiasts into an inclusive financial infrastructure for a broader population.

In Conclusion

$3.35 billion is essentially the tuition fee paid by the entire industry in 2025.

This also reminds us that as the industry begins discussing compliance, institutional interfaces, and mainstream capital inflows, if Web3 accounts remain in a state of “sign/approve once and get drained,” then the so-called financial infrastructure is merely built on sand.

The real question might not be “Will AA become mainstream?” but rather—if accounts do not evolve, how much future can Web3 still bear?

This might be the most thought-provoking security revelation that 2025 leaves for the entire industry.

This article is sourced from the internet: $3.35 Billion ‘Account Tax’: When EOA Becomes a Systemic Cost, What Can AA Bring to Web3?

The market is widely betting that an interest rate cut is almost a certainty. However, what will truly determine the trend of risk assets in the coming months is not another 25 basis point cut, but a more crucial variable: whether the Federal Reserve will inject liquidity back into the market. Therefore, this time, Wall Street is not focusing on interest rates, but on balance sheets. According to predictions from institutions such as Bank of America, Vanguard, and PineBridge, the Federal Reserve may announce this week a $45 billion monthly short-term debt purchase program starting in January, as a new round of “reserve management operations.” In other words, this means the Fed may be quietly restarting an era of “disguised balance sheet expansion,” allowing the market to enter a period…